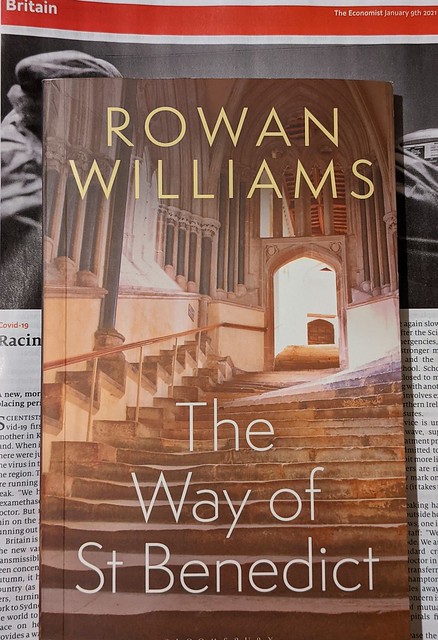

Weirdly, calling it "The Way of St Benedict" didn't trigger "Benedictine" to me at all. Given to us for Christmas by J. The cover shows "the worn steps leading up to the Chapter House, Wells Cathedral" and this is very much how I envisage the book, and Dr Williams: in an old but immaculately clean and maintained stone building, dimly arched above but nonetheless filled with light; sonorous; we are perhaps in his book-lined study, or in the SCR with old portraits looking down; the discussion is serious and reverential; people agree, or disagree politely. The bits of the book that fit this are a pleasure to read and can be said to work. The bits that attempt to go out into the real world are a failure. My picture subtly hints at this; the background is The Economist on Covid. You might like to read the Church Times review. Skimming wiki's Rule of Saint Benedict and finding the motto of the Benedictine Confederation: pax ("peace") and the traditional ora et labora ("pray and work") my feeling is that RW has been somewhat selective in what he has taken from The Way; but, it is his book.

Weirdly, calling it "The Way of St Benedict" didn't trigger "Benedictine" to me at all. Given to us for Christmas by J. The cover shows "the worn steps leading up to the Chapter House, Wells Cathedral" and this is very much how I envisage the book, and Dr Williams: in an old but immaculately clean and maintained stone building, dimly arched above but nonetheless filled with light; sonorous; we are perhaps in his book-lined study, or in the SCR with old portraits looking down; the discussion is serious and reverential; people agree, or disagree politely. The bits of the book that fit this are a pleasure to read and can be said to work. The bits that attempt to go out into the real world are a failure. My picture subtly hints at this; the background is The Economist on Covid. You might like to read the Church Times review. Skimming wiki's Rule of Saint Benedict and finding the motto of the Benedictine Confederation: pax ("peace") and the traditional ora et labora ("pray and work") my feeling is that RW has been somewhat selective in what he has taken from The Way; but, it is his book.Here's a nice quote from the intro:

The chapters in this little book will, I hope, help to flesh out in various ways something of the appeal of Benedictine life. It speaks to people of the extraordinary power of stability - not a static and frozen style of life, but a solid commitment to accompany one another in the search for a way to live honestly and constructively together in the presence of God. This stability is expressed in the habitually prosaic language of the Rule: it is about acquiring 'tools' for living accountably alongside others, for learning how to pay attention to others, for identifying and rectifying your own unthinking self-centredness. The undemonstrative, practical climate of the Rule has a particular attraction whenever talk about the spiritual becomes cloudy, elevated and unspecific. It is a good Benedictine principle that the call to common-or-garden faithfulness to one another has to be answered before there is any talk of supposedly higher callings: committed life together matters more than any individual search for spiritual fulfilment. But at the same time, that life together is the solid foundation for growth into intimacy with God, into what people call the 'mystical'; Benedict, in a typically low-key way, ends the Rule by gesturing towards the more radical adventures for which the teachings of the Desert Fathers and Mothers prepare the spirit. His point is simply that unless you have got yourself accustomed to the 'toolbox' of daily attention to the awkward reality of human others, the search for deeper intimacy with God will lead to destructive illusion.

That all reads well. For me, there's an awkwardness at the end of that passage: as an atheist, I have no God. This, I suspect, undermines my understanding of their fundamental point. If it helps you to understand me: when I think of this, and imagine myself quietly living out my dotage in a monastery - which often seems like a rather appealing idea, as I kinda imagine it like college cloisters - or like Anathem - then I think of myself as contemplating quantum mechanics. Or perhaps Lisp.

To illustrate the kind of things the book doesn't provide: I found myself wondering, if the monastic life (TML) and rule is so good, isn't it a regrettable failing of the Christian life that it isn't available to everyone? Do we see TML as better than "normal" life? Sometimes it seems like he does think this, but of course can't say so; but we get images of it "illuminating" normal life; or helping to keep the Church on track. P 30 has "the monastic life as a sharpening of the focus that exists in all Christian life" - this I think is his thinking, and makes sense if you go along with it, but doesn't actually have a clear meaning.

Part of TML is obedience to the abbot. RW speaks of this as though it were absolute; and perhaps it is; but that power would be corrupting to any mortal, and I don't think he explores problems with that. It also places huge burdens on the abbot, and RW just assumes that these will be borne ("he is accountable to God", says RW, which may satisfy the religious). This, on reflection, is rather close to Plato's philosopher-kings, who will make wise decisions; Popper I think decisively destroys this as idea but RW shows no awareness of this. As you can tell, I'm interested in issues of governance; RW isn't; they are to him an awkward side-issue from holiness, his main concern.

Stability was in the intro and is in chapter two: The Rule of Benedict is, in one sense, all about stability. That is to say, it's all about staying in the same place, with the same people. The height of self-denial, the extreme of asceticism, is not hair shirts and all-night vigils; it's standing next to the same person quietly for years on end. This is an interesting aspect, and a contrast with our outside world, where we are accustomed to change - or to attempt to change; or to be told that if we only vote for X then they will change for us - things that we don't like. I think however that this somewhat drops out when he comes on to talk about The Real World, later. And I'm mostly interested in how this could play out in TRW.

In contrast to stability of TML, RW comments we currently live in a world of almost unimaginable financial instability. We have created a seemingly unmanageable engine of chaotic change, governed by a small elite who will determine the patterns of international institutions; but this is not true. Is is a common leftist-progressive trope, and I'm sure whenever RW says it at nice dinner parties all the nice people attending duly nod their head an agree; but he needs to broaden his circle of acquaintance. Happily, RW has no answers to this problem and indeed nothing to say on the subject, so he soon drops it.

Chapter 3 fragment: "The truth of any ideas or doctrines is something that becomes apparent in the light of the sort of life that those ideas make possible". Accustomed as I am to a scientific worldview, this seems false. Even of philosophical ideas, it seems dubious. And I'm fully prepared to believe that people can lead good lives through belief in God, even though I think they're wrong. So I think I'm forced to fall back on him using "truth" is what I'd consider an odd way; perhaps "proof" would be better.

Chapter 5 attempts to take the Word out into the World. We discover that Outside, Time is an undifferentiated continuum in which we either work or consume. Work follows no daily or even weekly rhythms but is a 24-hour business. WTF? Was has he been smoking? After a bit he seems to realise that he's talking nonsense, because he adds "At least, that is the message regularly given by advertising and popular fictions" but really, he's off the rails and needs to just delete this bit. Or get some better editors.

In attempting to address Europe's problems he ventures onto migrants: to pick up point that is especially pertinent in our present situation, it would be one that did not panic about migrants. The migrant group that is prepared to work within the civic framework of a host society, that aspires simply to citizenship, is one whose voice in the community overall is of significance alongside those who have a longer history and a political or economic advantage. Once within the relationships of purposeful common life, the facts of coming from ethnically or religiously different backgrounds should not disenfranchise them. But this, whilst splendidly tolerant, really doesn't address any issues in any useful way. Could he perhaps have considered the analogy with a monastery? What would such do, if confronted by a group outside its doors, demanding admittance and attempting to scale the walls? He doesn't even consider this, and indeed he doesn't have any answers, offering only that "the way is open to a properly 'Benedictine' questioning" - but this is the approach of the academic, who has a scholarly interest in questions, because revolving possible solutions to questions is a fascinating intellectual pursuit.

Name checking Hegel favourably loses him points; refer to The Open Society and Its Enemies if this isn't immeadiately clear to you.

While I'm nearby, one of the abbot's tasks is to find the sort of labour appropriate to the capacity of each is perhaps appropriate in the small world of the monastery, but a poor model for govt; see Hayek. It isn't clear if RW is just being somewhat careless here, or isn't aware that the monastic order really can't scale up.

How am I to read work is the sustaining of a properly human and intelligent corporate ecology? Does the word "is" imply that what follows it, is a definition of the word "work"? If so, it seems idealistic. It might be what we desire work to be, given that most people spend large parts of their day doing it. The text may be referring back to an earlier A civilized life structured around the vision of the Rule is one in which economics is not allowed to set itself up as a set of activities whose goals and norms have no connection with anything other than production and exchange. This is a rather primitive or left-wing view of economics. Economics is the study of people's choices. In the free market model, they get to choose their own goals; I feel that RW would like them to choose better, and perhaps nudge them more or less powerfully to ensure this; fortunately, his abbot is not only Good but also Powerful, so nothing could go wrong with this. Elsewhere, he recognises the "centralising and impersonal pull of bureaucracy" but has no ideas of how to counter it. A little later he bashes globalisation, without of course noticing its role in bringing people out of poverty.

And how on earth did he come to write If the Rule is to be one of the sources for the conservation and renewal of European civilization in the centuries to come - granted that these centuries may be every bit as brutally anti-humanist as the so-called Dark Ages..? This is also somewhat odd: We cannot take it for granted that any political order, European or otherwise, will regard it as a priority to make possible a life of contemplative delight in God the Father. Indeed, I think we can be pretty sure that this will not happen. Hopefully that won't interfere with his programme too much.

Anyway, I think that gives you an idea of the book and my reactions. That covers part 1. As TLS notes (fortunately just before we hit the paywall), These pieces occupy two-thirds of the book. The remaining third reprints, with changes, two considerable essays written decades ago. I found them somewhat less interesting, only skimmed them, and will not attempt to review them.

No comments:

Post a Comment